In this application note, the use of the ACQUITY UPLC system combined with a SYNAPT G2-S Mass Spectrometer, to provide specific and unambiguous identification of the components present in citrus juices.

The presence of flavonoids in citrus juices has attracted attention because of their biological and physiological benefits. Flavonoids are one of the largest and most widespread classes of compounds that possess diverse pharmacological and biological properties. Such attributes mean many plant species containing flavonoids may be used as functional foods or phytomedicines. The role of flavonoid compounds as markers is important, and identification is a challenge due to sample complexity. Flavonoids are related to the prevention of cancerous processes, reduced risk of some chronic diseases, prevention of cardiovascular disorders, as well as anti-viral, anti-microbial, and anti-inflammatory activities, thus, emphasizing the reason for interest in flavonoids and the constituents of fruit juices. Typical sources of flavonoids are fruits, vegetables, and cereals. Considering these associated health benefits, the impact of food processing and preparation on flavonoid content demands a greater understanding. It is, therefore, essential to be able to profile all major and minor components of fruit juice to enable a better understanding of dietary consequences. Also, the impact of important factors that can influence consumers, such as appearance and taste, influence the commercial value of a product.1

Using HPLC-MS to profile flavonoids has become more commonplace. In this application note, the use of a Waters ACQUITY UPLC system combined with a SYNAPT G2-S Mass Spectrometer, to provide specific and unambiguous identification of the components present in citrus juices. High Definition Mass Spectrometry (HDMS) has been utilized to profile citrus juice products, and this technique offers some unique advantages for profiling complex mixtures. It is a combination of high resolution mass spectrometry and high efficiency ion mobility based measurements and separations. Ion mobility spectrometry (IMS) is a rapid, orthogonal gas separation phase technique that provides another dimension of separation within an LC time frame, offering higher ion definition and analytical specificity. Compounds can be differentiated based on size, shape, and charge, as well as mass.

Tangerine juice samples were filtered through a 45-μm filter.

|

LC System: |

ACQUITY UPLC |

|

Column: |

ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 150 x 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm |

|

Column temp.: |

40 °C |

|

Flow rate: |

0.4 mL/min |

|

Mobile phase: |

MeCN (B): H2O (0.2% HCOOH) (A) |

|

Time (min) |

Flow rate |

%A |

%B |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Initial |

0.4 |

99 |

1 |

|

0.75 |

0.4 |

95 |

5 |

|

5 |

0.4 |

5 |

95 |

|

5.5 |

0.4 |

99 |

1 |

|

Injection volume: |

10 μL |

|

MS System: |

SYNAPT G2-S |

|

Ionization mode: |

ESI - at 2.7 kV |

|

Sample cone voltage: |

30 V |

|

Desolvation temp.: |

650 ˚C |

|

Reference mass: |

Leucine enkephalin, [M-H]- =554.2615 |

|

Acquisition range: |

50 to 1200 m/z |

|

Acquisition rate: |

5 spectra/sec |

|

Collision energy ramp: |

33 to 45 eV |

|

Resolution: |

18,000 FWHM |

|

IMS T-Wave velocity: |

550 m/s |

|

IMS T-Wave pulse height: |

40 V |

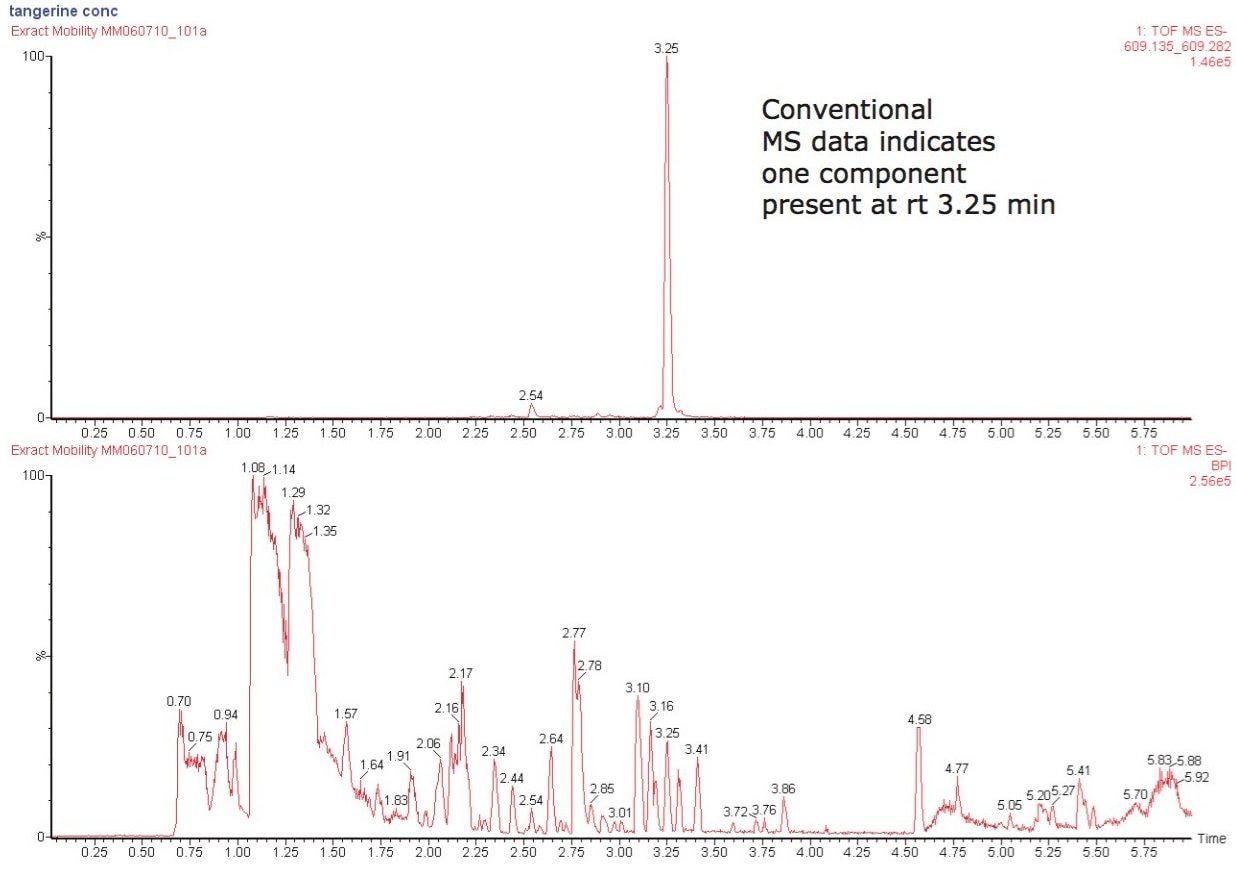

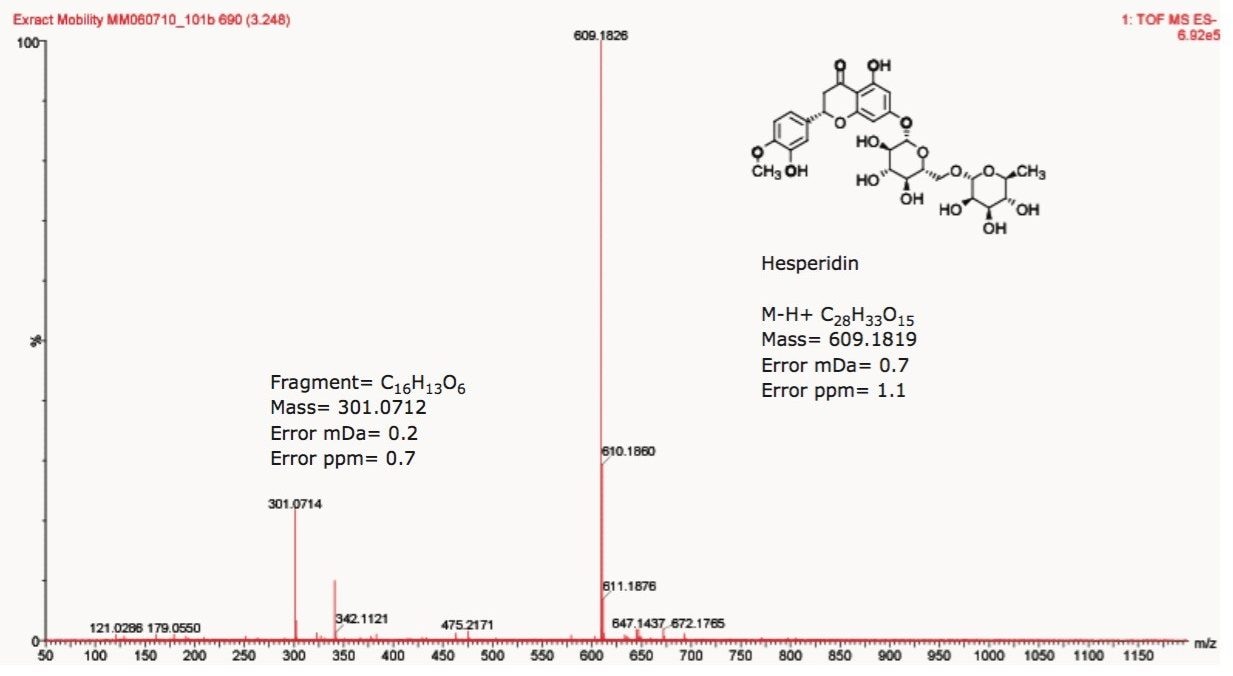

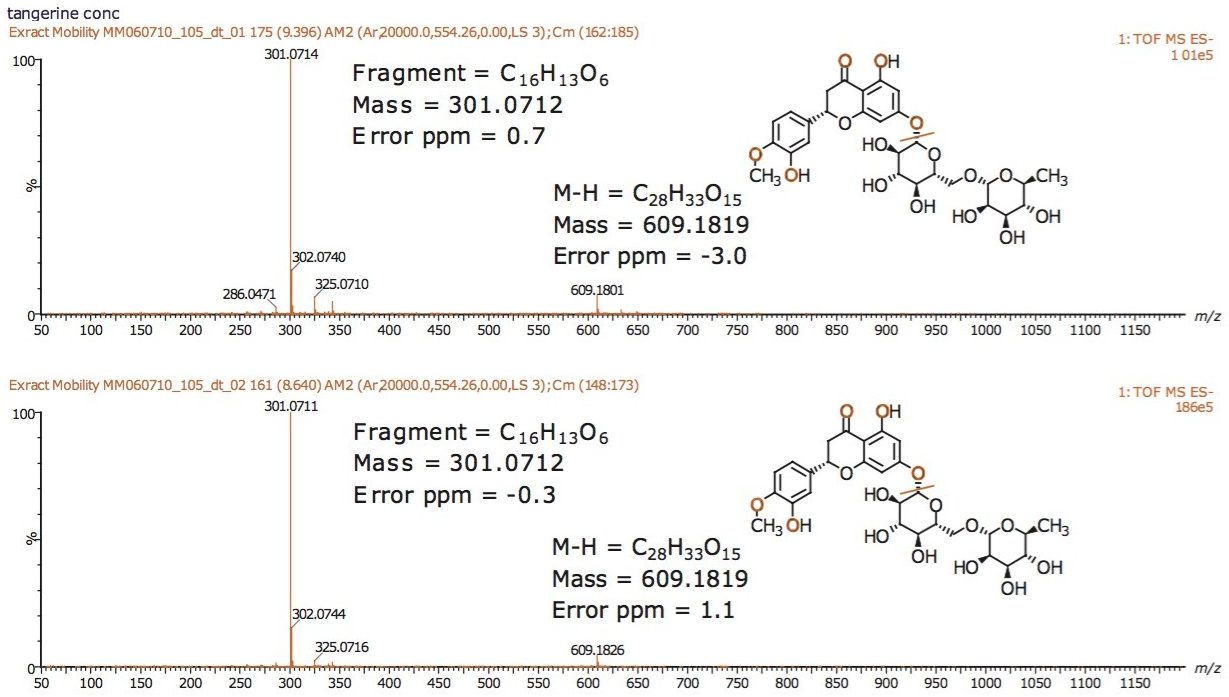

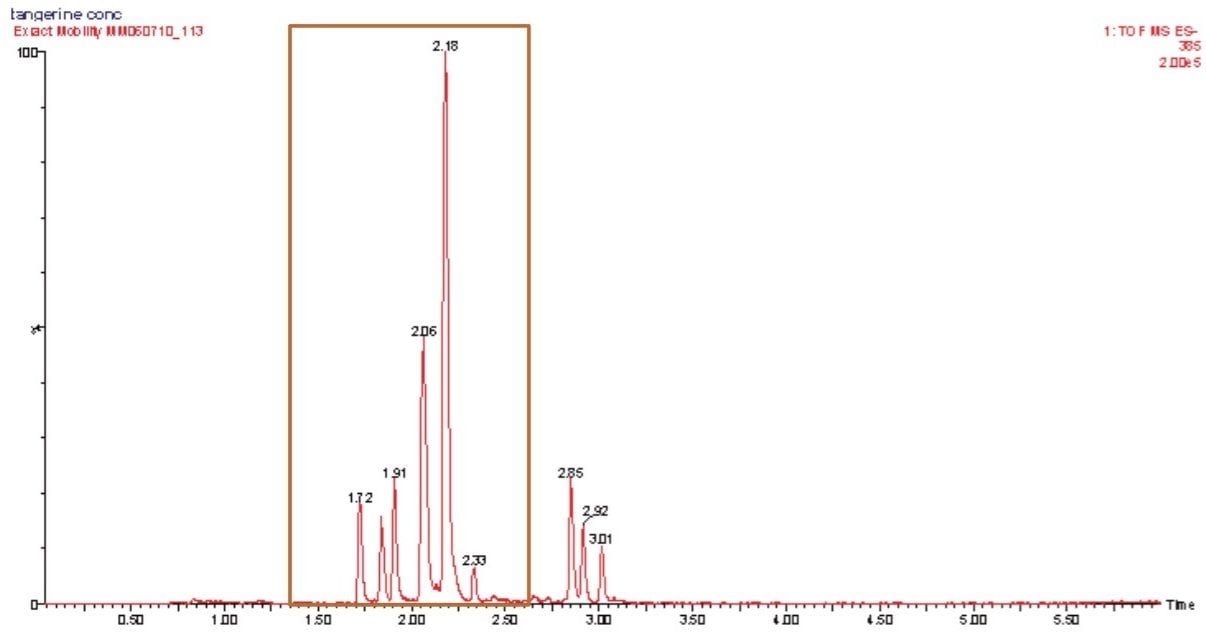

Using a SYNAPT G2-S with UPLC-IMS/MSE functionality, the components of tangerine juice were profiled using negative ion mode electrospray. IMS provides an extra dimension of fast, gas phase, ion separation, with higher ion definition and analytical specificity. IMS has been described as “gas phase electrophoresis.” The profiling study undertaken clearly shows the benefits of using HDMS. Figure 1 shows the conventional negative ion mode base peak intensity (BPI) chromatogram and m/z 609 extracted mass chromatogram obtained for the analysis of undiluted tangerine juice. The corresponding accurate mass spectrum is shown in Figure 2. The accurate mass spectrum generated elemental compositions of C28H33O15 (1.1 ppm error) and C16H13O6 (0.7 ppm error). Utilizing the elemental composition generated, a ChemSpider search was performed; whereby, a likely candidate for the component at 3.25 min was believed to be hesperetin 7-O-rutinoside (hesperidin). Under the conditions used, the peak at m/z 301.0714 was caused by source fragmentation and occurred due to the loss of the disaccharide moiety. The fragment observed, and accurate mass/elemental composition generated aided structural elucidation.

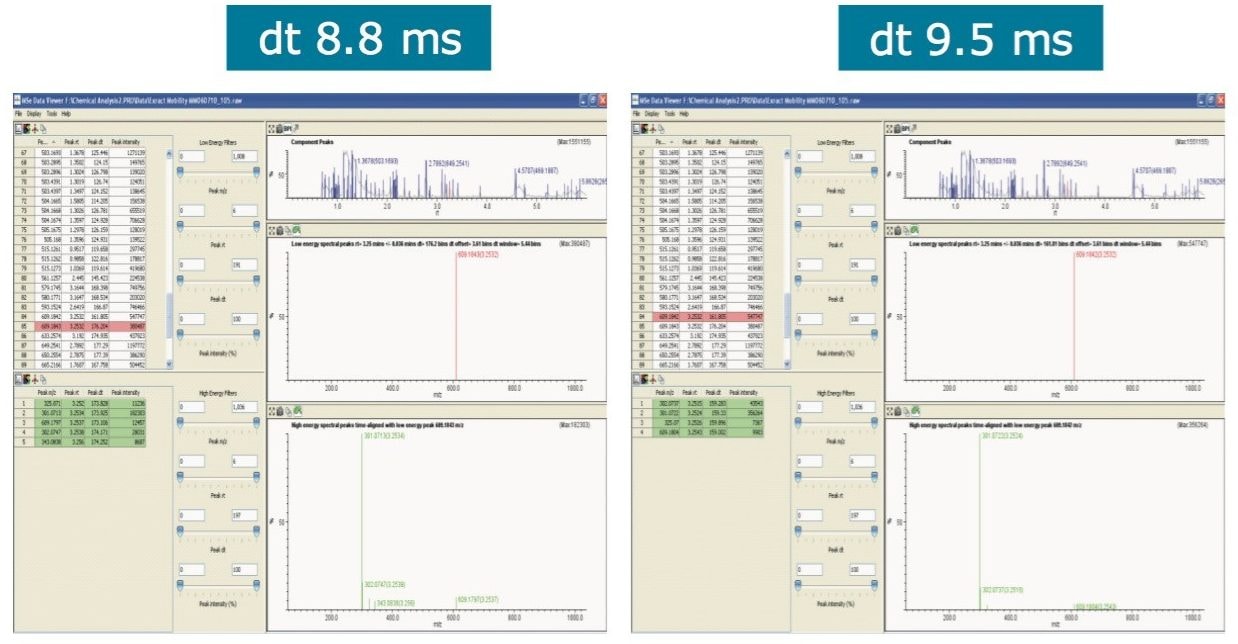

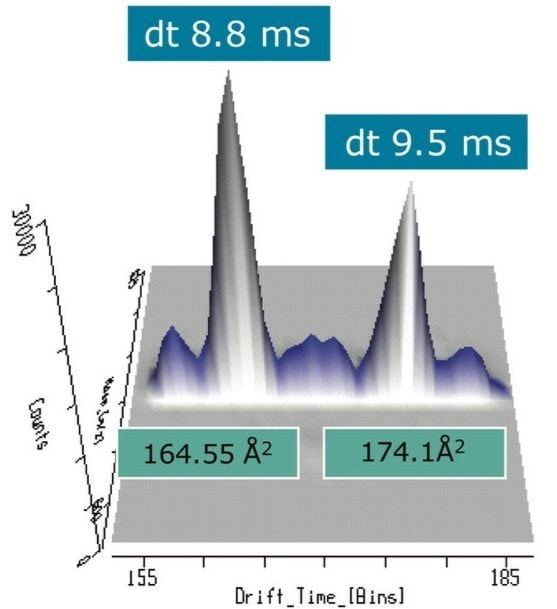

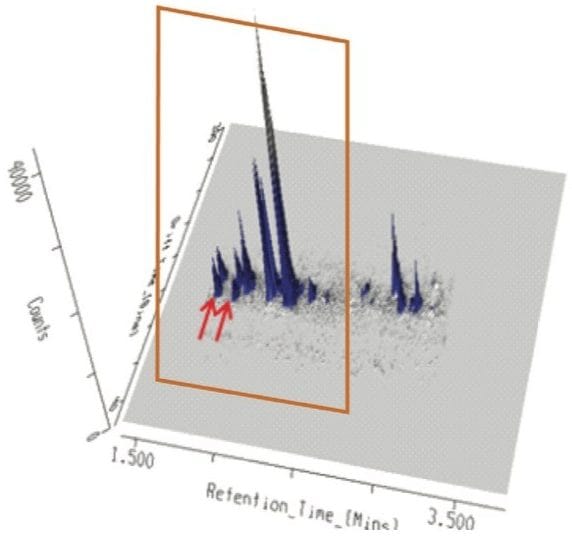

When this data was viewed through the MSE data viewer, the component at 3.25 min proved to be more interesting, and was actually comprised of two components. The MSE data viewer displayed the peak detected BPI for tangerine juice with mobility data revealed two components present at 3.25 min, as shown in Figure 3. The precursor ion and fragmentation spectra are generated from two different drift times, and the resulting 3D data display for the ion mobility separation achieved for these isobaric components are shown in Figure 4. The MSE data viewer enables time-aligned high and low energy spectra generated through MSE acquisitions to be seamlessly viewed. In addition, where mobility separations have been generated, the mobility separation and spectra can be accessed. The software also enables isobaric components with different drift times, but the same retention time, to be visualized at the click of a button. Utilizing this filter, it was possible to see instantly that within this extremely complex sample, comprised of 930 major and minor analytes, the peak at 3.25 min was actually two components. Drift times of 8.8 ms and 9.5 ms were observed, allowing the estimated T-Wave collision cross sections (CCS) of the components to be determined to be 164.6Å2 and 174.1 Å2, respectively.

UPLC-IMS/MSE was performed where collision induced dissociation (CID) fragmentation was performed in the “transfer” region of the “Triwave”; hence, structural elucidation data was generated for the two IMS isobaric components in 3.25 min. The MSE fragmentation spectra for the mobility resolved isobaric components is shown in Figure 5, displaying the same fragmentation patterns. Under these conditions, a minor fragment at m/z 463 was observed, which can be attributed to the loss of the rhamnose sugar unit from the m/z 609 precursor ion and then m/z 301 from the further loss of the glucose unit to generate the aglycone at m/z 301. The data generated indicates that the conformers of hesperidin were observed.

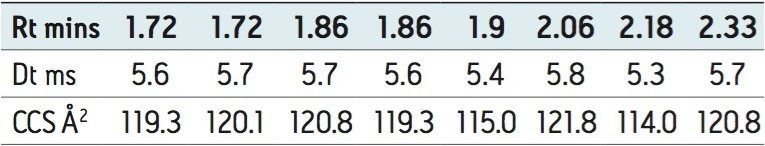

A further example is shown in Figure 6, where the conventional negative ion mode m/z 385 extracted mass chromatogram obtained for the analysis of tangerine juice can be seen. The corresponding 3D mobility data is displayed in Figure 7. The first two peaks of the conventional extracted mass chromatogram were comprised of four IMS components. Examples of the estimated T-wave CCS values generated, shown in Table 1, indicate these values can be utilized to provide further characteristic profiling data.

The results obtained indicate that IMS can provide increased peak capacity, and more component identification. IMS combined with MSE enables specific and unambiguous identification of mobility separated components.

720004462, October 2012